Yeow Kai Chai (b. 1968)

FEATURES / TRACK CHANGES

A Riff on Dualities

Written by Yeow Kai Chai

Dated 30 Jul 2020

“Couplets” is among numerous poems using the couplet form in my second collection, Pretend I’m Not Here (2006). I have a fondness for the couplet—I remember listening to an interview with American poet John Yau who said he enjoyed writing in couplets because the poem immediately looked accessible and approachable, and readers were inclined to link the couplets even if they aren’t meant to be.

That’s how I wrote “Couplets”, a commentary on couple-dom, or more accurately, a voyeur’s observation on a young couple and the ritual of courtship, loaded behavioural stereotypes, heteronormative baggage, and the trickery of power negotiation. When I was approached for this editing/revising project, I immediately thought of this poem. To me, it’s like a short film, edited like a music video.

So, my approach is to recut the poem as if I’m a film editor. I wanted to push the idea of duality more. The twin cinema comes to mind. I had written my first twin cinema, “Begone Dull Care”, in 2010, four years after “Couplets” was written. For me, the form itself is rooted in the idea of two or more simultaneous screenings. While other folk have taken the form and made it leak-proof (to be read three ways), my initial impulse is to expose its leakiness, the gap between clauses and columns, and by extension, the human impulse to make the links, to make sense of it all. A twin cinema is best appreciated by reading it out loud in endless ways, including, yes, diagonally. The experience is as much about elision as it is about connection.

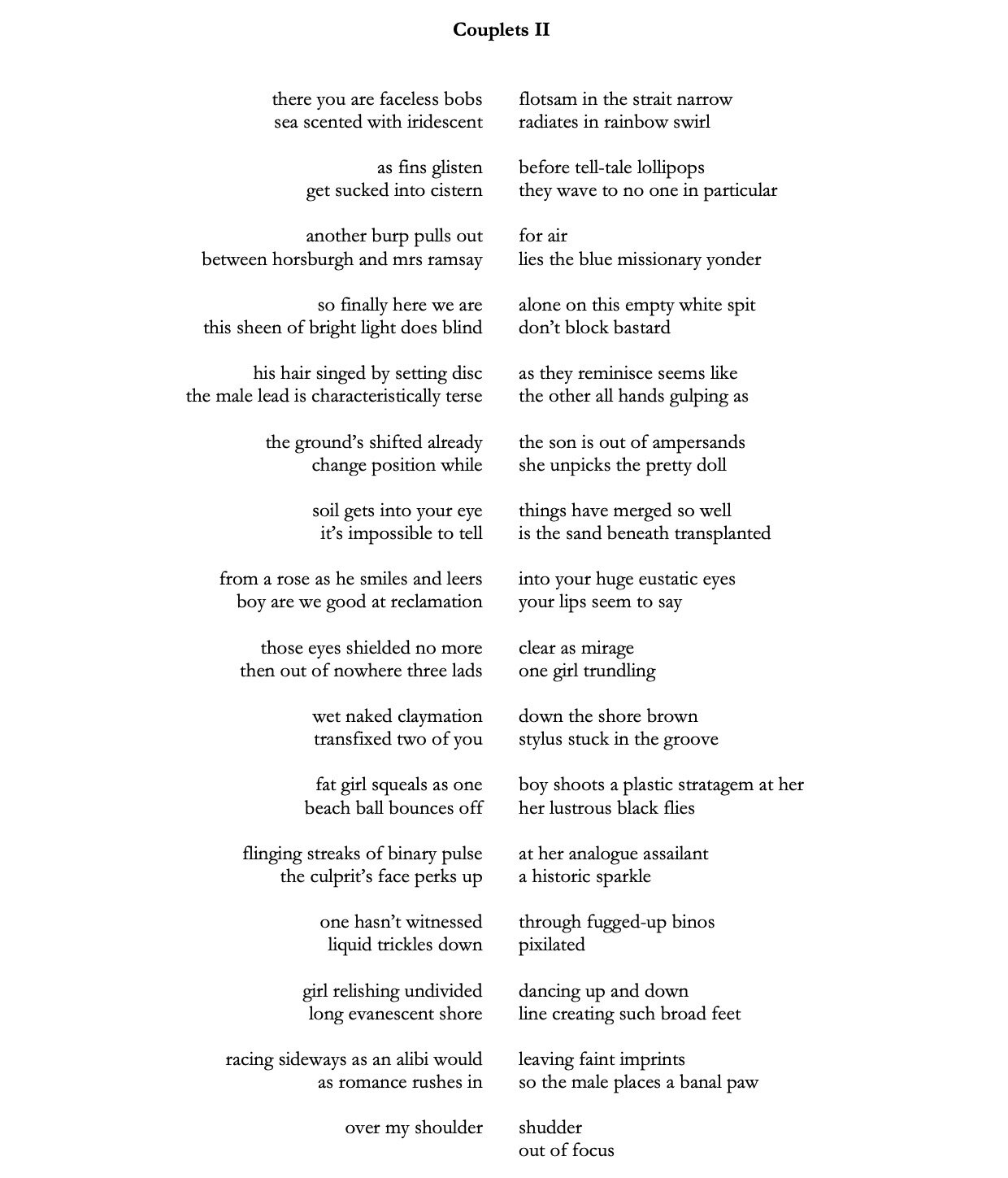

Thus, “Couplets II”:

The original lines are draped across two columns, from left to right, and with the couplet form retained. Each couplet is a cinematic vignette which melts into another. Pronouns are tossed around to create a disorientating effect, as if the camera is swerving from one point of view to another (bystander, participant, villain, hero, damsel), and through whose eyes we are witnessing the scene. Is this scene completely innocent, even corny, or is there a more sinister subtext?

I did not make that many word changes. In some cases, I took out certain words, so as to enhance the staccato/truncated effect, while in others, I tweaked a word or two, either replacing it or changing its grammatical tense, in order to create flow, or to be more open-ended, and hopefully less dogmatic.

For instance, in the first couplet, first line, right column, “like” was thrown out. So was “oil” in the first couplet, second line, left column. In the second couplet, fourth line, left column, “are” was replaced by “get”. In the fifth couplet, first line, left column, “the” was removed, and in the same stanza, first line, right column, “it” was taken out.

In the sixth couplet, second line, left column, I took out “even”, and in the same couplet, second line, right column, “and” is removed. In the seventh stanza, first line, left column, one line is entirely removed – the self-referential question “where is the old non-sequitur” – to be replaced by the more vivid and sensorial image, “soil gets into your eye.”

In the 13th couplet, first line, left column, “for” is dropped, and in the first line, right column, “light years” is gone. In the 13th couplet, second line, left column, “trickling” becomes “trickles” while in the second line, right column, “corrugated forehead” is replaced by “pixelated,” a riff on “pixie”, or the ‘manic pixie dream girl’ archetype in films.

Recasting the poem makes me ask the question: How could I make use of the twin cinema form to bring out the qualities that film does so well: changing perspectives, mirror and refract, and the power of suggestion, sometimes without words? As a poet, though, I have to use words, but I don’t have to view them as static things. In the Barthesian sense, words can be divorced from their meaning. They are surrogate tools, or props, for me to set up the scene, lure the reader-viewer in and ultimately make him or her complicit in the whole shenanigan.